Copy of article from MyMobile

Shelley Vishwajeet | September 12, 2018

Much like most parts of the world, the e-commerce phenomenon has overwhelmed the Indian retail landscape too. But is the rapid rise of their popularity and market share purely an outcome of the technological march, fair play and the emergence of a democratic marketplace benefitting all stakeholders alike as was stipulated or is it due largely to factors, which ethically and legally, are in grey zone but helped e-commerce gain an undue advantage over the physical retail!

Amid serious allegations of unfair trade practices leading to unprecedented disruptions, we take a look at the e-commerce phenomenon as it stands today in India and what the government needs to do to create a level playing amongst various stakeholders.

The case for e-commerce was built around promising premises! Consumers would get a never before choice and convenience; retailers would get a cheap, equitable market platform with unprecedented reach; the government would get enhanced tax as tax evasion would minimize with every transaction being on the record. To top, it was supposed to open a whole new world of possibilities. Thus a sculptor infusing life into stones by a sea-side village in coastal Odisha could reach directly to an aficionado of traditional craft in Bengaluru; the organic produce form Sikkim would reach homes in Gurugram; a small mobile handset dealer in Noida could clear his excess inventory at marginal discount without too much worry as to from where he will get customers or his inventory becoming obsolete while a customer in Varanasi could lay hands on the biggest spread of shoe brands which he could not get in his city or for that matter Mrs Anamika Srivastava who prefers to use authentic spices from Malabar coast could order the same without much ado! And all this at the click of a mouse with no parking or bargain hassles while shopping at one’s one time and leisure!

E-commerce marketplace was supposed to herald a new era of democratic marketplace where all stakeholders – be it consumers, retailers, the government – would be winners. It was supposed to be a win-win proposition for all. Thus the great democratic disruptor was to be welcomed despite some anticipated discomforts to the old order. The reality, however, has turned out to be quite different!

And, not only in India, e-commerce platforms were supposed to be the gateway to the world for the Indian retailers and entrepreneurs. It was supposed to democratize the marketplace while expanding its universe. The whole world was to become their playground! It was to be the down of a new era!

“To circumvent FDI rules, Flipkart and Amazon have created multiple companies, and the government must stop such activities. What is not allowed directly cannot be done indirectly” – Vikram Mittal, Secretary, Telecom Watchdog.

Yet, the policymakers also knew that despite all the promise and new possibilities, the new order would cause disruption from which larger stakeholders needed to be given a fair shield – whether they be India’s humungous conventional brick and mortar retailers – the backbone of the economy or be they be the common consumers. Thus, a policy note called Press Note 3 of 2016 (PN3/2016) was decreed which was supposed to be the lighthouse for e-commerce operations in India. PN3/2016 permitted no inventory based trading for e-commerce platforms; it also (the amended press note) stated that no one retailers would be allowed to sell more than 25% of the total value of one product on one e-marketplace. The stipulations were supposed to offer adequate protection to conventional Indian retail landscape while offering a democratic and equitable access to all sellers and consumers.

But soon the reality turned out to be different. As E-commerce start gaining foothold rapidly, especially after the direct entry of Amazon in 2012 aided by rising income, increased internet penetration and smartphones, the contour of this space also started changing. So as billions began to be poured into larger e-commerce platforms, it became a high stake game with furious competition between players for creating consumer base and retailers listing. The race to the top made had its fallout. The e-commerce platforms, particularly the big daddies like Amazon, Flipkart and Snapdeal went into ‘innovation mode’ to circumvent the regulations. They started acquiring the character of e-tailers rather than being simply an e-commerce marketplace, although taking care to unleash the new game via select ‘third parties’ who they either fostered or patronized. A game of market distortion fuelled by questionable marketing practices and humungous discounts began which soon became a cause of concern for physical retailers and the government alike. In this scenario, consumers and e-commerce platforms had a field day but the physical retailers, small retailers registered with these e-commerce platforms and the government were big losers. Particularly in high value, high selling items such as mobile, electronics goods, clothing, etc e-commerce share zoomed up.

Back in 2012, when Amazon had just begun testing the Indian retail waters via Junglee.com, an ‘online retail sites discovery platform’ it had acquired in 1999-2000, Flipkart was struggling to clock an annual sale of Rs 500 crores (approx 70 million USD) while the total value of online merchandise was estimated to be less than USD half billion. Around that time, no research body or soothsayer was predicting the kind of online implosion or the market disruption that was about to begin. But by 2016, the total value of online merchandise had crossed USD 15 billion. Zoom in to 2017 and the value had more than doubled! According to a report by Morgan Stanley, online retail in India could grow to over USD 200 billion by 2026, which will be something like 12% of India’s overall retail market!

“Inventory model leads to the creation of monopolies as big global players offer to buy products from sellers at an attractive price initially, but squeeze their margins later when these small sellers are entirely reliant on them” – Dharmendra Kumar, Director, India FDI Watch

On the ground too, there was nothing really to suggest at the time that the Indian online market would evolve so dramatically as to send the entire retail space into a tailspin. India’s traditional retailers – the brick and mortar masters – ones who had dominated India’s retail landscape since time immemorial had little inkling of the disruption that was in the making. Little surprising, they saw no need to prepare for a battle nobody could see nor anticipate!

And as one would expect, the impact of online marketplace has been far bigger in metros and tier-I cities where incomes are high coupled with higher smartphone ownership and digital penetration and time is at a premium. These factors according to a KPMG report had given a massive fillip to online commerce. The biggest impact was seen in high value and high selling items such as mobile phones and electronics goods. Studies by Counterpoint Research and e-Marketer estimated that online sales constituted more than 40% of total smartphones sales in India in 2017 and its share was going to become bigger, spurred by never before super discounts and frequent sale weekends.

The murmur of discomfort amongst conventional retailers had begun with the rise in popularity of e-commerce but it was the massive cornering of lucrative categories such as electronics and mobiles by big online platforms that really put conventional retailers in the anxiety zone. The contention of conventional retailers was that the fast shrinkage of their market share was not primarily an outcome of the digital march but largely a fallout of the unfair trade practices being employed by e-commerce entities which in all practicality had become e-tailers via pseudo entities.

Vikram Mittal, Secretary, Telecom Watchdog is certain that there is no ambiguity in the PN-3/2016. “To circumvent FDI rules, Flipkart and Amazon have created multiple companies, and the government must stop such activities. What is not allowed directly cannot be done indirectly,” says Mr Mittal.

He further says that marketplaces have to be a neutral place and e-commerce entities cannot indulge in influencing price including discounts with or without the association of brand product owners. “All their actions and contrary the rules and as such they are illegal.”

Dharmendra Kumar, Director, India FDI Watch too echoes the same concerns. “India does not allow FDI in B2C e-commerce, nor does it permit inventory based e-commerce model for the marketplace. But big players have been practicing inventory based model by patronized third parties.” He also points out that the ‘inventory model’, leads to the creation of monopolies as big global players offer to buy products from sellers (largely MSME players) at an attractive price initially, but squeeze their margins later when these small sellers are entirely reliant on them.

Some serious allegations leveled against e-commerce platforms included (i) Circumvention of Press Note 3/2016 which relates to FDI rules in e-commerce space (ii) Indulgence in inventory based trading via third parties which is not permitted under Indian laws (iii) Cartelization and operations through pseudo distributors/sellers entities to corner market share (iv) Market distortion via heavy discounts (v) Tax evasion stratagems.

Worried market watchers point out that these practices have not only marginalized small retailers, brought undesirable disruptions in Indian retail landscape, but would also lead to loss of mass employment. For brand owners too, experts point out that by indulging in short-terms gains by joining hands with large-ecommerce entities, brands over time would lose their power and hold and would just become a pawn in the hand of e-commerce companies.

To repudiate these charges and to be part of this critical story, we reached out to Amazon, Flipkart and Snapdeal. Unfortunately, only Amazon responded by stating that they do not wish to offer any comment while Flipkart and Snapdeal did not respond to our mails!

The Modus Operandi:

Notwithstanding the amazing success and growing footprint, the E-commerce marketplace has become an enigma for the retailers and policymakers alike. Dr Rashmi Das in her book, “E-com in India: Violations & Tax Avoidance” points out that since inventory-based trading is not permitted, to circumvent this rule, large e-commerce platforms created multiple entities or associated with “Name Lending” companies through which they started routing hot-selling stocks.

Mr Vikram Mittal explains that via the ‘Name Lending’ companies, the e-commerce platforms buy the branded goods in bulk (at discounts) from manufacturers rendering small sellers uncompetitive by a wide margin, thus influencing the prices in violation of FDI norms. As a consequence of this FDI norms violation, smaller sellers are unable to participate in the fast-growing e-commerce sector. Because of subsidized prices on e-commerce platforms, the retailers are unable to sell in the brick and mortar world too.

The cumulative impact of this is that the marketplaces have usurped the space meant for small retailers by turning into proxy sellers. “It is ironical that the marketplaces, meant to help smaller sellers grow online have crowded them out of not only e-commerce but also out of the brick-n-mortar world,” says Mr Mittal.

The Structural Puzzle:

Experts explain that creation or adoption of a web of companies large e-commerce companies by-pass FDI rules and for tax dodging purposes has been the most common and contentious practice. Mr Mittal unravels the structural labyrinth created by these companies. “When a consumer tries to buy something from Amazon, he is routed to www.Amazon.in, which is owned & operated by a company called Amazon Seller Services Pvt Ltd (“Amazon Seller”), which is a marketplace. This is an entity of concern say market experts. The other entity of concern is Cloudtail India Pvt Ltd (‘Cloudtail’). It is registered as one of the sellers on the website of Amazon Seller (the 3rd entity). Cloudtail is the largest seller on Amazon Seller. In FY 2015-16, it ended with a revenue of Rs 4,591 crore, while Amazon Seller posted a revenue of Rs 2,275 crore. In FY 2016-17, Cloudtail has posted revenue of Rs 5,706 crore while Amazon Seller has posted revenues of Rs 3,257 crore. Cloudtail has reported a loss of Rs 26.67 crore, and Amazon Seller’s loss is Rs 4,831 cr. With such a high revenue, they pay no tax. And while FDI is not allowed in an entity operating on inventory based e-commerce model but Cloudtail is essentially doing this. It is registered as one of the sellers on Amazon Services.”

Besides the above, Amazon arranges discounts to its customers by utilizing the following process. “Amazon Wholesale India Pvt Ltd (AWIPL) will buy branded goods in bulk from a manufacturer of mobile phones, electronics, white goods, branded fashion etc. AWIPL will sell the goods to Amazon controlled sellers like Rocket Commerce, Green Mobiles at a discount and will book the resultant loss in its books. Amazon Seller Services will pay for marketing (print & TV advertisements), exchange offers, Zero cost EMIs and some part of bank offers and will book these expenses in its books. Amazon Seller Services will undertake all logistics related tasks (including packaging, shipment to buyers, returns, liquidation of damaged goods, compensation to sellers, cost of payment gateways etc.). All these expenses are booked in its books – against an average cost of Rs 250 per packet, only about Rs 125 is recovered by Amazon Seller Services, thus influencing the price charged to the consumers via this subsidy.”

A similar route has been undertaken by Flipkart to gain market share points out Mr Mittal. “The flipkart.com was owned by Flipkart Online Services Pvt Ltd (FOS). In June 2009, founders set up WS Retail Service Pvt Ltd as the company’s consumer-facing entity and FOS was turned into a wholesale cash-and-carry business. In 2011, FOS sold its entire business (brand, technology, employees and business contract) to Flipkart India Pvt Ltd. Since then, Flipkart has added several other entities. Flipkart Internet Pvt Ltd now owns the domain name Flipkart.com. Flipkart Internet does not sell products itself. Its revenue comprises listing fees and other platform services provided to third-party vendors, including WS Retail. It is now being taken over by US retail giant Walmart.”

To avoid payment of income taxes in India, the Bansals established their holding company in Singapore called as Flipkart Pvt Ltd (“FPL”) says Mr Mittal. The ownership of FPL largely rests with US-based hedge fund Tiger Global, Accel Partners, Naspers and the Bansals. Some of its entities registered in Singapore as 100 percent subsidiaries of FPL are: Flipkart Marketplace Pvt Ltd, Flipkart Logistics Pvt Ltd and Flipkart Payments Pvt Ltd. These companies, in turn, hold stakes in Indian entities through a complex maze of companies. This was deliberately done to circumvent the ban on FDI in online retail in India.

WS Retail is one of the most important pieces of the Flipkart puzzle says Mr Mittal. “With as little as Rs 90.50 lakh capital, WS Retail could achieve a turnover of Rs 13,921 crore in FY16 and got away by paying a meager sum of Rs 1.89 crore as income tax!”

WS Retail was owned by the Bansals until Sep 2012. They along with two of their relatives were on the board of WS Retail. In Nov 2012, Flipkart was forced to sell a large stake in WS Retail to Rajeev Kuchhal, former COO of OnMobile Global Ltd, when the Indian regulatory agencies launched an investigation into the company’s business relationship with WS Retail. Both the Bansals and their relatives gave up their board seats too.

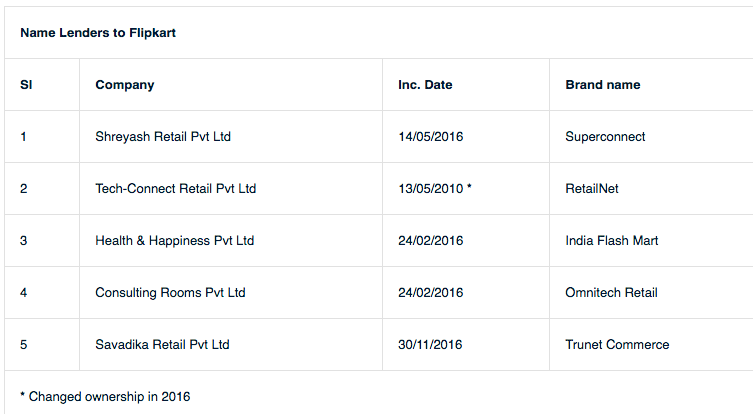

After the PN-3/2016, Flipkart devised a new method under which it looked for some Name Lenders who would form companies and through them, the invoicing for goods would be routed. Out of several thousands of brands registered on their website, database analysis showed five brands that appeared frequently and also did not have much or no competition in their respective categories on Flipkart’s online marketplace. To avoid any direct linkages, Flipkart used completely different brand names, which have no correlation with the names of their respective companies. For example, Superconnect is the brand name that appears on the Flipkart screen, but its company name is Shreyash Retail Pvt Ltd.

Needed A Level and Fair E-Market Place:

Given such practices, it is no surprise that e-commerce marketplaces were able to gain undue advantages over the conventional Indian retailers with ease and in double quick time. It is also disheartening to note that a new era of democratic marketplace which e-commerce platforms were supposed to usher never really happened. This certainly is a cause of concern and does not augur well for the long-term interest of Indian economy. One really wished that the government and regulators had been more proactive to check the malpractices and circumvention of FDI rules and regulations.

“If the goal can be achieved through existing laws, then maybe we should focus on that. For example, strengthening the ED to enforce the FDI policy and bringing in clarity on the FDI policy’s implementation would solve a lot of the issues” – Arjun Sinha, Legal Experts & Partner, Cantor Associates

Thankfully, the rising concerns ultimately forced the government to set up a committee at DIPT under Ministry of Commerce, GoI to come out with a concrete set of laws and regulation for regulating e-commerce marketplace. The government recently gave the first insights into its thinking and has invited suggestions. Arjun Sinha, legal experts, and Partner, Cantor Associates says that the government should first take a cue from the several laws and regulations which are already in place while it needs to focus on enforcement. “Strengthening the ED to enforce the FDI policy and bringing in clarity on the FDI policy’s implementation would solve a lot of the issues. One also has to note that there are also several types of e-commerce businesses that already have a fair amount of regulation (even for e-commerce companies) – such as insurance, transport or food delivery. Here not only how the business is conducted, but licenses and permits required, pricing and liability related issues are also addressed by the sectoral regulations,” says Mr Sinha. He also notes that as a nation we need to identify the goals we want to achieve before bringing in new regulations. “If the goal can be achieved through existing laws, then maybe we should focus on that.”

“Allowing limited inventory to e-commerce platform is not at all acceptable since they are only technology facilitators and nothing to do with inventory. If they are allowed to keep inventory, it will distort the basic fundamental of the policy” – Praveen Khandelwal, Secretary General, CAIT

Praveen Khandelwal, Secretary General, Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT) is quite categorical that new policy on e-commerce must not allow inventory based model directly or indirectly, partial or via third party, at any cost.

“Allowing limited inventory to e-commerce platform is not at all acceptable since they are only technology facilitators and nothing to do with inventory. If they are allowed to keep inventory, it will distort the basic fundamental of the policy. The term ‘bulk purchases’ currently is ambiguous and as such needs to be defined and clarified. The e-commerce companies should not be allowed to offer any discount since they are not the owners of inventory. Each e-commerce company should be duly registered with authorities,” says Mr Khandelwal.

Amid this, the silver lining is that the government is looking at all issues with an open mind. “The government has an open mind regarding e-commerce policy and based on suggestions and inputs received from the stakeholders, the second draft of the e-commerce policy would be placed in public domain likely in next fortnight,” Mr Sudhanshu Pandey, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Commerce and Industry had recently stated while addressing a national convention of physical retailers.

“There should be a fair competition between offline and online trades. These trades must be given equal status” – Sudhanshu Pandey, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, GoI

Mr Pandey had also raised some points to ponder. “Most e-commerce sites in India mainly sell imported goods due to which local industries and products are impacted. What if some foreign investor said he or she is ready to pump in money into a marketplace that specializes in goods that are produced locally?” In effect, what Mr Pandey was implying that Indian needed to have laws that permit all kinds of healthy possibilities, rather than completely shutting the door for future explorations. But the most comforting note by him was that he agreed on the need to create a level playing field between online and physical retailers. “There should be a fair competition between offline and online trades. These trades must be given equal status.”

We too hope that the new e-commerce regime would be a more transparent, equitable and a real democratic space for all stakeholders!

With Inputs from Ramesh Kumar Raja & Nijhum Rudra